Silencing Song: Music and Genocide

Understanding the destruction of art and music as a central weapon of genocide

Ethnocide refers to the systematic destruction of a group's cultural practices, expressions, and institutions. While genocide is commonly understood as the physical elimination of a people, mass violence often includes deliberate efforts to erase the cultural foundations that sustain collective identity. Cultural practices such as music, ritual, language, and artistic expression function as mechanisms of continuity and social cohesion; their removal can undermine a community as effectively as physical displacement or death.

In many cases of mass atrocity, perpetrators target these cultural forms to weaken communal bonds, eliminate markers of distinctiveness, and disrupt the transmission of memory between generations. The suppression of artistic expression, the destruction of cultural artefacts, and the prohibition of rituals serve not only as tools of domination but also as strategies for reshaping or nullifying a group's presence in history.

This study examines how music and art become focal points in such processes. It considers the ways in which perpetrators attempt to silence cultural expression and how victims engage these same forms to maintain identity, resist oppression, and document their experiences. Understanding the cultural dimension of mass violence clarifies that the destruction of art is not an incidental by-product of conflict but a central component of ethnocide.

The Spectrum of Violence: Just War vs. Genocide vs. The Holocaust

Traditional warfare operates under certain constraints, at least in theory. Just War doctrine, particularly the principles of jus in bello, establishes boundaries: combatants are legitimate targets, civilians are not. Cultural sites—temples, libraries, concert halls—fall under protection. When such places are damaged in conventional conflict, it is classified as collateral damage or prosecuted as a war crime. The objective remains military victory, not the elimination of an identity.

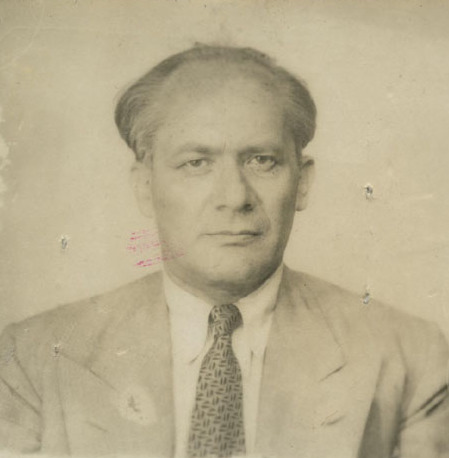

Genocide represents a fundamental shift. Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term in 1944, understood genocide as a coordinated plan aimed at destroying the essential foundations of the life of national groups. In his foundational work Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, Lemkin described genocide as having two phases: "one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor." This formulation made clear that genocide targets not only biological existence but also the social, cultural, political, and economic structures that sustain group life.

Lemkin's definition extended beyond mass killing to encompass what he termed cultural genocide—the deliberate destruction of a group's language, religion, culture, and national consciousness. He argued that such destruction could occur even without widespread physical extermination, though the two typically proceeded together. The enemy is no longer defined by uniform or weapon, but by ethnicity, religion, or culture. Military victory becomes insufficient; the goal is elimination. The target expands to include anyone who carries the identity—children, elderly, intellectuals, artists.

The Holocaust established the industrial benchmark for such total destruction. The Nazi regime did not merely kill Jews—it burned their books, banned their music as "degenerate," and transformed cultural artifacts into tools of humiliation and torture. Music played in concentration camps served not to comfort but to mock, to accompany forced labor, to mark the march to gas chambers. This systematic approach to cultural annihilation created a framework that helps illuminate similar patterns in other mass atrocities. The Holocaust demonstrated how thoroughly a regime could pursue not just physical but existential elimination, validating Lemkin's insight that genocide attacks both the body and the culture of its victims.

Ethnocide: Killing the Spirit

Lemkin's concept of cultural genocide, though ultimately excluded from the 1948 UN Convention on Genocide due to political pressures, provides essential language for understanding how mass violence operates. Cultural genocide—or ethnocide—describes the destruction of culture, the ethnos, as distinct from but complementary to physical genocide. While genocide kills people, ethnocide kills the patterns that make those people recognizable as a group. The two often proceed together, each reinforcing the other's aims.

Music and art become prime targets because of their functional role in group maintenance. Music coordinates collective action, marking celebrations, rituals, resistance. It transmits history in cultures where oral tradition dominates over written records. Art serves as a physical repository of memory—icons, manuscripts, instruments carry centuries of accumulated meaning. A single cantor or qewal may hold knowledge that exists nowhere else.

Destroying these carriers creates a specific kind of void. Even if individuals survive the initial violence, they return to find their cultural infrastructure demolished: the musicians dead, the instruments smashed, the sacred texts burned, the shrines reduced to rubble. The community loses its capacity to reconstitute itself, to pass knowledge forward, to maintain continuity with what came before. This is why genocidal regimes consistently target intellectuals, artists, and religious figures early in their campaigns. Kill the carriers, and the culture itself becomes terminally vulnerable.

Lemkin himself emphasized this dimension in his analysis of Nazi occupation policies across Europe. He documented how the Germans systematically suppressed Polish education, prohibited Ukrainian cultural institutions, and destroyed Yugoslav cultural monuments—measures designed to eliminate national consciousness even where mass killing was not the primary tool. These examples illustrated his argument that genocide encompasses attacks on the cultural and institutional life of groups, not merely their physical existence.

These principles manifest differently across contexts, shaped by the specific cultures targeted and the methods of those pursuing their destruction.

The Erasure of Ancient Heritage: The Armenian Genocide

The Armenian Genocide of 1915-1923 represented the first modern systematic attempt to erase a people from their ancestral lands. The Ottoman government did not simply deport or kill Armenians; it pursued the deliberate destruction of the cultural markers that had defined Armenian presence in Anatolia for millennia. This case profoundly influenced Lemkin's thinking—he later stated that his interest in genocide began with learning about the Ottoman campaign against the Armenians.

The campaign began with the arrest and murder of Armenian intellectuals, writers, and community leaders in Constantinople on April 24, 1915. This decapitation of the cultural elite served a calculated purpose: it severed the community's connection to its own documented history and artistic traditions. Poets, musicians, and scholars who had maintained links to centuries of Armenian culture were eliminated systematically.

Churches and monasteries—repositories of manuscripts, liturgical music, and sacred art—were destroyed, converted, or left to ruin. The architectural footprint of Armenian civilization was methodically erased from regions where Armenians had lived for thousands of years. Musical traditions, passed through families and religious institutions, were disrupted as the communities that sustained them were scattered or killed. We explore the systematic destruction of these cultural pillars in our feature on Art and the Armenian Genocide.

The Holocaust in Microcosm: Bogdanovka

The Holocaust in Transnistria offers a particular window into how cultural perversion accompanied mass murder. Bogdanovka, a concentration camp in occupied Soviet territory, became a site where the mechanisms of the Holocaust played out with distinct characteristics.

Here and throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, the relationship between music and murder took on systematic dimensions. Orchestras composed of prisoners were forced to perform as others were marched to execution. Music—once a marker of civilization and transcendence—became an instrument of mockery and control. The Nazis weaponized cultural forms, using them to humiliate victims while maintaining a veneer of order and efficiency in the killing process.

This represented not merely the destruction of culture but its deliberate corruption, transforming art into an accessory to atrocity. It exemplified Lemkin's observation that genocide involves the destruction of the national pattern—not just killing Jews, but annihilating the cultural forms through which Jewish life expressed itself. A stark example of this intersection of music and mass murder can be found in the history of Bogdanovka.

The Betrayal of Media: The Rwandan Genocide

The 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda demonstrated how modern media could accelerate cultural and physical destruction. Radio Télévision Libre des Milles Collines (RTLM) broadcast continuous incitement, using popular music and familiar voices to normalize murder. Singer Simon Bikindi's songs, which had celebrated Hutu identity, were repurposed as anthems of extermination, played repeatedly as the killing unfolded.

This represented a dual assault through sound: traditional music was either silenced or co-opted for propaganda, while new messages of hate saturated the airwaves. The speed of the genocide—approximately 800,000 people killed in 100 days—was facilitated by this sonic campaign that reached into homes and vehicles across the country, creating a shared soundscape of violence.

The manipulation of musical culture showed how art forms that normally bind communities together could be twisted to identify and target victims. Musicians who might have preserved alternative narratives were killed or forced into silence. The destruction encompassed both the physical elimination of Tutsi and the cultural apparatus through which Rwandan society had previously understood itself. In Rwanda, we see how media and song were weaponized to incite violence, as detailed in Music and the Rwandan Genocide.

The Assault on Oral Tradition: The Yazidi Genocide

The ISIS campaign against the Yazidis beginning in 2014 represented an explicit attempt at religious and cultural extinction. Yazidism relies almost entirely on oral transmission—sacred knowledge passes through qewals (religious singers) and is maintained at holy sites. Written scripture is minimal. This made the culture particularly vulnerable to a specific form of attack.

ISIS systematically targeted the carriers of this knowledge: qewals were killed, captured, or forced to flee. Shrines at Lalish and elsewhere were destroyed or desecrated. The goal was not merely to kill Yazidis as individuals but to permanently delete their religion from history. If the singers died and the shrines were destroyed, how would the prayers be remembered? How would the next generation learn the hymns?

This represents perhaps the clearest contemporary example of cultural genocide as Lemkin conceived it. The destruction of oral tradition means that even survivors become disconnected from their own cultural inheritance, unable to perform the rituals or teach the songs that defined their community. The attack on Yazidi culture demonstrates how groups whose identity depends on non-written transmission face acute vulnerability to ethnocide. Most recently, the targeted destruction of oral history is evident in our analysis of Musical Culture and the Yazidi Genocide.

The pattern across these cases reveals a consistent logic: perpetrators understand that cultural destruction amplifies physical violence, making recovery more difficult and erasure more complete. Lemkin's formulation of genocide as both physical and cultural attack provides a framework for understanding why the silencing of song is not a side effect of genocide but one of its primary instruments. The destruction of cultural forms serves the broader aim of eliminating groups not only from the present but from historical memory itself.