Oskar Posa: A Composer Silenced

Oskar C. Posa (1873-1951), once a central figure in Vienna's musical circles, experienced a dramatic fall from prominence that effectively erased him from music history. Born Oskar Posamentir in Vienna on January 16, 1873, to a Bohemian father and Viennese mother, Posa had established himself as one of Austria's most promising composers by the turn of the twentieth century.

Pre-War Musical Career

Before the war fundamentally altered his trajectory, Posa occupied an influential position in Viennese musical life. He co-founded the Society of Creative Musicians (Vereinigung schaffender Tonkünstler) in 1904 alongside Arnold Schoenberg and Alexander von Zemlinsky. Contrary to long-held assumptions, recent research reveals that Posa, not Schoenberg, authored the founding memorandum for this organization. The society, which counted Gustav Mahler as its honorary president, represented a musical response to the Jugendstil movement and paralleled the Vienna Secession in the visual arts.

Posa composed more than seventy songs and lieder, works that captivated audiences across Europe and the United States. Critics described his compositions as "piano compositions with voice accompaniment," noting their harmonic sensuality and pianistic complexity. His songs fused elements from Brahms and Wagner, creating what contemporaries recognized as strikingly original works.

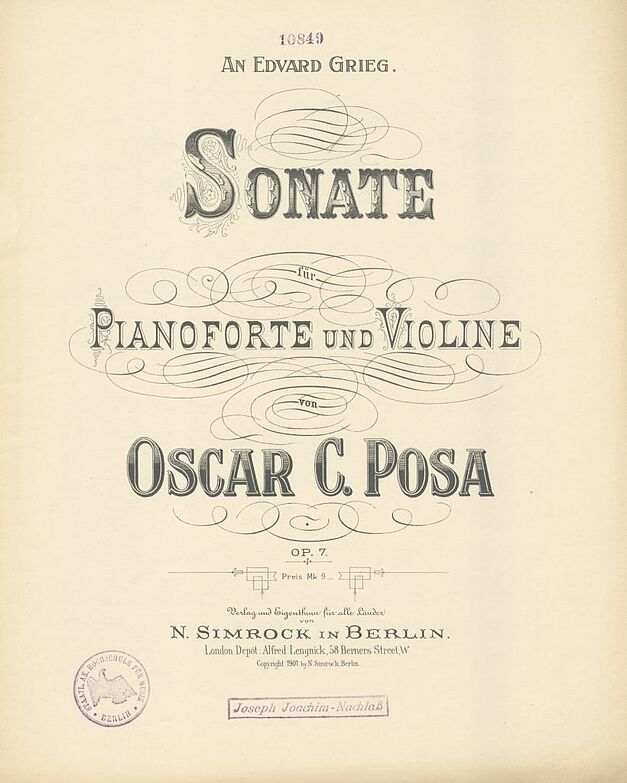

At the height of his career, disaster struck with the public premiere of his Violin Sonata in 1901. The work, recognized for its genius but presenting almost superhuman technical demands, collapsed into catastrophe during its performance at the Heidelberg Music Festival. This failure plunged Posa into a profound depression that marked a turning point in his career.

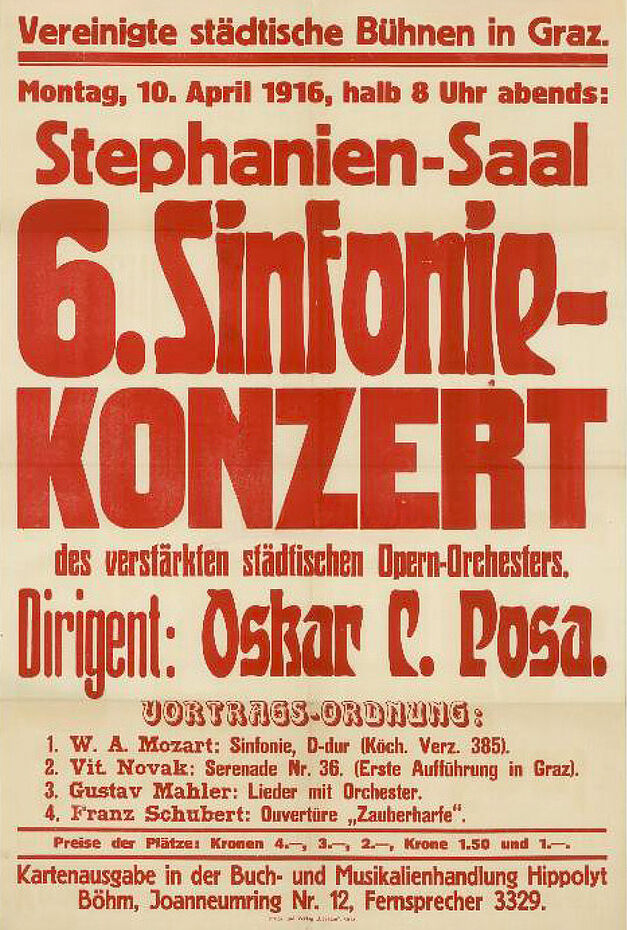

Despite this setback, Posa rebuilt his reputation over the following decades. He served as principal conductor at the Graz Opera, Austria's second largest opera house, from 1911 to 1913, where he also led symphonic performances. He later received his doctorate in Vienna and was appointed professor at the prestigious Vienna Conservatory, gradually re-establishing his position in Austria's musical establishment.

Wartime Persecution and Silencing

Posa's position at the Vienna Conservatory had been secured through the influence of Anton Rintelen, a controversial figure who served twice as governor of Styria and briefly as Austrian federal minister of Education in 1933. Rintelen had known Posa during his conducting years in Graz and used his political connections to create a specialized teaching position for the composer at the Vienna Conservatory, where from 1933 Posa taught operatic role preparation as a vocal coach.

This protection proved fragile. In July 1934, Rintelen became implicated in a Nazi putsch aimed at assassinating Austrian Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss and facilitating German annexation. Though the coup failed and Rintelen was sentenced to life imprisonment for high treason, he received amnesty just one month before the Anschluss.

On March 11, 1938, Hitler's troops annexed Austria. Four days later, Alfred Orel, a Brucknerian musicologist and ardent nationalist, was appointed interim director of the Vienna Conservatory with orders to purge Jewish teachers and those deemed politically undesirable. Posa was summoned and ordered to justify his origins.

When questioned, Posa presented a Catholic baptismal certificate dated 1897, when he was 24 years old. Orel found this late conversion suspicious and pressed for explanations. Posa claimed the certificate contained a clerical error and should read 1879, not 1897. Orel systematically dismantled this defence, noting that the godfather listed was Dr. Karl Dorrek, a financial adviser who would not have held that position in 1879. In his report to the Ministry of Education, Orel concluded that Posa's explanation constituted "an attempt to dissimulate his Jewish origins."

On April 7, 1938, just five days after his interrogation, Posa was suspended from his teaching duties. His definitive dismissal came on June 1. From that day forward, his music was never performed again publicly.

The systematic erasure continued through bureaucratic channels. In 1940, musicologist Herbert Gerigk compiled the "Lexicon of Jews in Music" for the Nazi regime, a dictionary designed to institutionalize the exclusion of Jewish musicians from cultural life. Surprisingly, Posa did not appear in the first edition. However, on January 11, 1941, a Nazi party official named Bury wrote to the publisher pointing out this omission, describing Posa as "Conductor, composer (partly published), a long-time resident of Graz." His name was included in the second edition, officially sealing his eviction from musical life.

Life in Internal Exile

After his dismissal, Posa remained in Vienna without employment, income, or means to leave the city. He entered what amounted to internal exile, living at the family home in Damböckgasse in Vienna's 6th district with his sisters Charlotte and Helene. His third sister, Elsa, was deported with her husband Ernst Khuner to the Theresienstadt concentration camp, which they survived.

In September 1945, barely four months after Germany's capitulation, Karl Kobald, the new director of the Vienna Academy of Music and Performing Arts, submitted a request to the Ministry to reintegrate Posa "by way of reparation." However, Kobald made this request without particular insistence, emphasizing mainly the composer's advanced age—he was then 72. The request came to nothing.

Final Years and Death

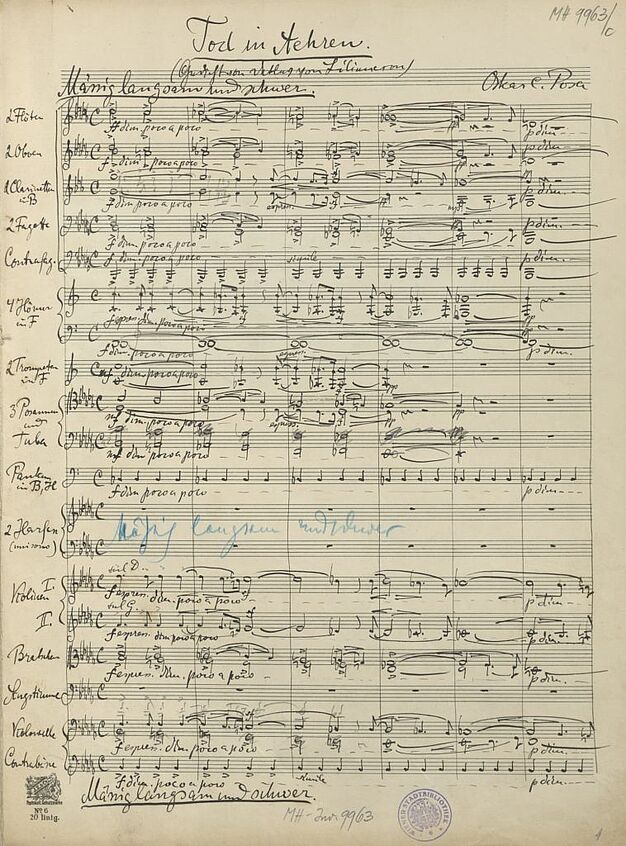

Late in life, in 1947, Posa returned to composition despite his circumstances. From this period came his final works: two songs for baritone and small orchestra (Edward and Ein Lied Chastelards), his String Quartet, op. 18, and a large-scale symphonic work, Praeludium und Fuga fantastica, op. 19, which remains lost.

Posa's financial situation had become desperate. He could not afford to pay his subscription to the AKM, Austria's copyright society, thereby forfeiting his right to collect royalties or apply for emergency support. A 1950 file from Viennese authorities considering an exceptional pension for the composer confirmed that "since his dismissal, his situation seems to have deteriorated more and more, with the result that he now lives in utter destitution."

Beyond this extreme poverty, little is known about Posa's final years. According to family accounts, he lived with two pet parrots, which may have caused his death from psittacosis, an avian disease with severe respiratory complications.

Posa died on March 15, 1951, in total anonymity. However, between his death and funeral, the city of Vienna suddenly recognized what he had once represented. In belated homage, he was granted a grave of honor—a perpetual concession—in the Zentralfriedhof, Vienna's central cemetery, alongside Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, Wolf, Zemlinsky, and Schoenberg. His scores and manuscripts found their place in the Vienna Library, housed in City Hall.

The composer's fate illustrates how political persecution could entirely erase a significant musical figure from history. Posa's story remained largely unknown until recent musicological research began uncovering his contributions to early twentieth-century Viennese music, revealing the extent to which his blacklisting had succeeded in removing him from the historical record.

Sources

Wolfgang Behrens, research on Oskar C. Posa (cited regarding Rintelen's protection and Posa's position at the Vienna Conservatory)

Alfred Orel, Report to the Ministry of Education, March 1938 (regarding Posa's interrogation and dismissal)

Nazi Party Central Office for Ideological Education, Letter from Bury to publisher, January 11, 1941 (regarding Posa's inclusion in the Lexicon of Jews in Music)

Karl Kobald, Request to Ministry for Posa's reintegration, September 1945

Viennese authorities file on exceptional pension consideration, 1950

Herbert Gerigk, Lexikon der Juden in der Musik (Lexicon of Jews in Music), 1940-1941

Correspondence between Oskar Posa and Julius Röntgen, April 18, 1904 (regarding authorship of the Society of Creative Musicians memorandum)

Neue Freie Presse, April 23, 1904 (publication of the founding memorandum)

Szmolyan, 1974 (regarding Schoenberg's letter to Posa, July 13, 1904)

Egon Wellesz, biography of Schoenberg (regarding the formation of the Vereinigung schaffender Tonkünstler)

Bruno Walter, autobiography (regarding the Society for Creative Musicians concerts)

Family accounts (regarding the pet parrots and psittacosis)