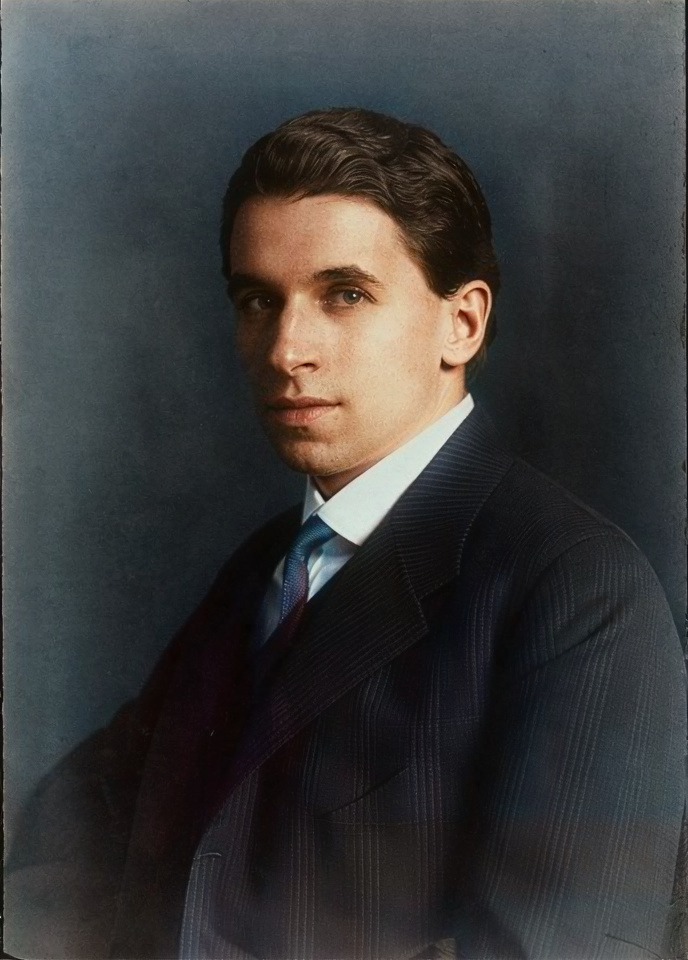

Erwin Stein (1885–1958) remains one of the most important advocates and editors of early twentieth-century modernism. Best known for his long association with Arnold Schoenberg and the publishing houses that carried the music of the Second Viennese School into circulation, Stein’s contribution reaches far beyond institutional roles. He shaped performance practice through meticulous reductions, clarified new compositional languages through writing and teaching, and preserved a threatened musical culture during an era of coercion and displacement.

Stein grew up in Vienna at a moment when the city’s musical institutions were expanding and its artistic networks were unusually porous. His formal studies placed him in contact with the leading theorists and performers of the city, but it was his decision to study with Schoenberg in the first decade of the century that defined his artistic identity. Schoenberg’s studio didn’t provide a narrow training in modernism or twelve-tone composition, but rather created a forum in which students learned to question inherited structures and balance expressive freedom with disciplined craft. Stein absorbed this dual emphasis and ultimately did not pursue a career as a concert composer. Instead, he developed the ability—rare then and now—to translate the complexities of new music into forms performers could approach with confidence, particularly as an editor.

His work with the Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (Society for Private Musical Performances) reveals this talent in its clearest form. The Society, active in Vienna from 1918 to 1921, sought to present new works in an atmosphere free from public hostility and journalistic sensationalism. Performances required detailed preparation and often depended on chamber reductions of orchestral scores. Stein was responsible for several of these reductions, including the celebrated chamber version of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony.[1] The reduction does more than thin a large ensemble; rather, it reveals Mahler’s contrapuntal clarity and formal transparency in a way that anticipates modern performance priorities. Stein approached such tasks with the precision of a craftsman and the awareness of a performer who understood rehearsal realities.

Also in the early 1920s, he joined Universal Edition, the most progressive publishing house in Central Europe. There he became a central figure in preparing complex vocal scores and instrumental materials for composers such as Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. Archival holdings at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum that document the Viennese musical press and cultural associations of the interwar years confirm Universal Edition’s centrality in disseminating new music and the vulnerability of its Jewish staff and partners as antisemitic policy intensified. Stein’s role at the firm required tact, technical discipline, and the ability to communicate the intentions of composers who were pushing the boundaries of form and harmony within an increasingly politically fraught system.[2]

During this same period Stein produced a series of essays that explained emerging compositional techniques with unusual lucidity. Instead of popularizing contemporary works, he sought to articulate the internal coherence of works that many listeners met with apprehension due to unfamiliarity with perceived dissonance or the movement away from romantic tonality. His writings emphasized motivic logic, careful control of musical space, and the evolving relationship between text and sound.[3] These essays circulated widely in German-speaking musical circles and helped establish an informed critical vocabulary for discussing twelve-tone composition and its precursors.

The Anschluss in 1938 abruptly changed Stein’s life. Like many Jewish intellectuals and artists, he became subject to expulsion from professional posts and to the forced liquidation of property. Materials preserved in both the USHMM and Yad Vashem on the reorganization of music publishing and the coordinated removal of Jewish employees from cultural life illustrate the pressures faced by individuals in Stein’s position. He left Austria soon after the annexation and settled in London, joining publisher Boosey & Hawkes. The transfer of musicians from Vienna to Britain, documented in refugee records held by Yad Vashem and in émigré registration files, created new artistic constellations, parallel to other exile networks in Los Angeles and New York. Stein became a key participant in London’s emerging modernist community.[4]

Meanwhile in Austria, the reorganization of Universal Edition following the Anschluss illustrates how cultural policy under National Socialism directly targeted the musical life of Vienna. Beginning in spring 1938, the firm was subjected to a systematic process of “Aryanization,” in which Jewish shareholders and senior staff were pressured or legally compelled to relinquish their positions and equity to approved non-Jewish owners. For Universal Edition, whose leadership and editorial staff included many Jewish or “politically suspect figures”, the measures were swift and disruptive. Stein, who had held both editorial authority and equity shares, was notified that his holdings would be placed under compulsory (Nazi) administration.[5] Internal correspondence from the period, later examined by historians of the Austrian music industry, describes tight deadlines, forced valuations, and political audits designed to remove Jewish participation while preserving the firm’s economic utility for the Reich. Austrian state commissioners oversaw personnel changes, dismissed long-standing employees, and reviewed the publisher’s catalogue for “undesirable” works — a classification that encompassed nearly the entire repertory of the Schoenberg circle. This dismantling of the firm’s intellectual core, combined with the risk of further sanctions, made Stein’s continued presence in Vienna untenable. His departure was thus not only a personal necessity but also part of the larger disintegration of the city’s modernist institutions under racially based cultural policy.

At Boosey & Hawkes, Stein took on wide-ranging responsibilities: preparing editions, advising on contemporary repertoire, and shaping the publisher’s understanding of central European modernism. His work intersected with British composers as well, most notably Benjamin Britten, whose meticulous approach to pacing and clarity resonated with Stein’s editorial values. Exile did not distance Stein from Schoenberg’s circle. Instead, he assumed a curatorial stance, ensuring that works by composers endangered or silenced by fascism could find performers, publishers, and audiences in their new cultural surroundings.

Stein’s writings after his arrival in Britain demonstrate a growing interest in the broader historical stakes of musical transmission. He helped found Tempo in 1939, a periodical intended to offer reliable commentary on contemporary music through concise essays and practical perspectives from editors, composers, and performers. The journal became one of the most consistent English-language sources on European modernism during wartime and postwar reconstruction.[6] In the 1950s he edited the first significant selection of Schoenberg’s letters, providing essential documentation for scholars and strengthening the historical record at a time when first-hand witnesses were rapidly disappearing.

His approach to editing was always guided by a concern for performers. Stein believed that clarity in layout and notation could determine whether a difficult score gained a foothold in repertory or fell into neglect. For music that relied on tightly organized motivic development, precise rhythmic profiles, and sharply differentiated instrumental colours, editorial decisions bore real interpretive weight. Stein’s editions reflect a consistent emphasis on balance and structural awareness. They remain models of intelligent mediation between composer and performer.

Stein’s family life is less documented in institutional archives than his professional activities, yet his household formed part of the broader network of Austrian musical émigrés in Britain. His daughter Marion became an accomplished pianist and later a significant figure in British cultural circles. Through such connections, the legacy of Viennese modernism persisted in informal as well as institutional ways.